California Senate President Pro-Tem Darrell Steinberg countered my Wall Street Journal commentary California Declares War on Suburbia in a letter to the editor (A Bold Plan for Sustainable California Communities)

that could be interpreted as suggesting that all is well in the Golden

State. The letter suggests that business are not being driven away to

other states and that the state is "good at producing high-wage jobs,"

while pointing to the state's 10 percent growth over the last decade.

Senate President Steinberg further notes that the urban planning law he

authored (Senate Bill 375) is leading greater housing choices and

greater access to transit.

This may be a description of the California past, but not present.

Exporting People

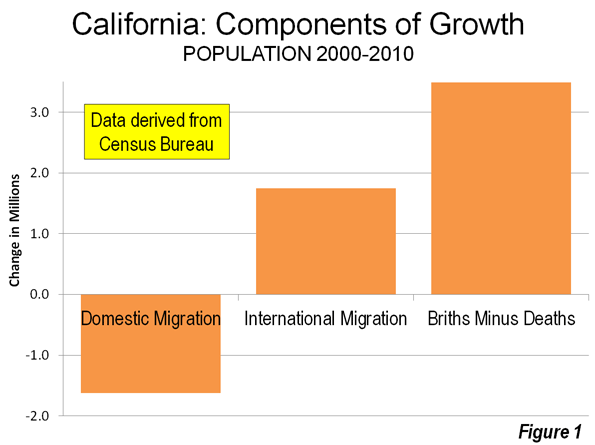

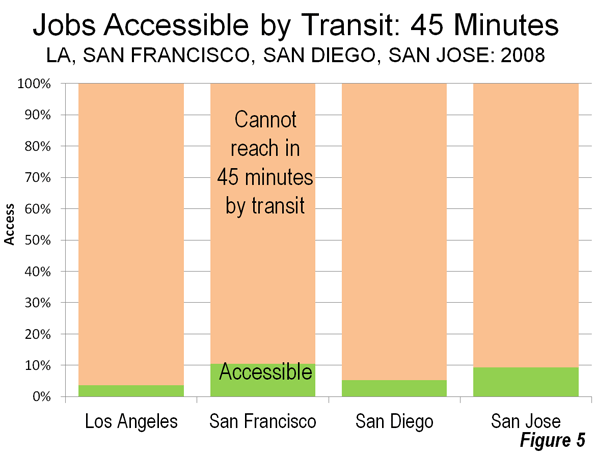

Yes, California continues to grow. California is growing only

because there are more births than deaths and the state had a net large

influx of international immigration over the past decade. At the same

time, the state has been hemorrhaging residents (Figure 1).

Californians are leaving. Between 2000 and 2009 (Note), a net 1.5

million Californians left for other states. Only New York lost more of

its residents (1.6 million). California's loss was greater than the

population of its second largest municipality, San Diego. More

Californians moved away than lived in 12 states at the beginning of the

decade. Among the net 6.3 million interstate domestic migrants in the

nation, nearly one-quarter fled California for somewhere else.

The bulk of the exodus was from the premier coastal metropolitan

areas. Since World War II, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Diego and San

Jose have been among the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the

United States and the high-income world. Over the last decade, this

growth has slowed substantially, as residents have moved to places

that, all things being considered, have become their preferences.

More than a net 1.35 million residents left the Los Angeles

metropolitan area, or approximately 11 percent of the 2000 population.

The San Jose metropolitan area lost 240,000 residents, nearly 14

percent of its 2000 population. These two metropolitan areas ranked

among the bottom two of the 51largest metropolitan areas (over

1,000,000 population) in the percentage of lost domestic migrants

during the period. The San Francisco metropolitan area lost 340,000

residents, more than 8 percent of its 2000 population and ranked 47th

worst in domestic migration (New York placed worse than San Francisco

but better than Los Angeles). Each of these three metropolitan areas

lost domestic migrants at a rate faster than that of Rust Belt basket

cases Detroit, Cleveland and Buffalo.

San Diego lost the fewest of the large coastal metropolitan areas

(125,000). Even this was double the rate of Rust Belt Pittsburgh.

Exporting Jobs

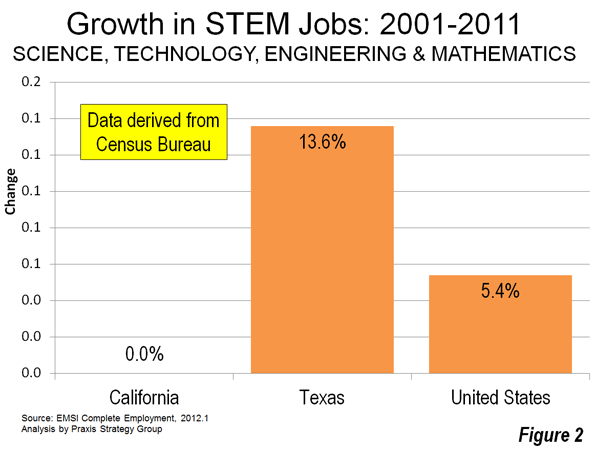

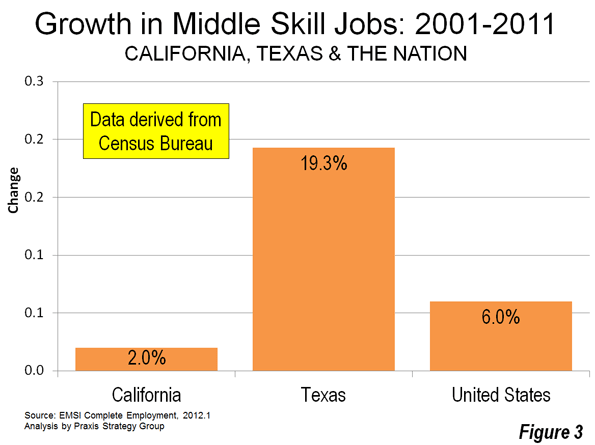

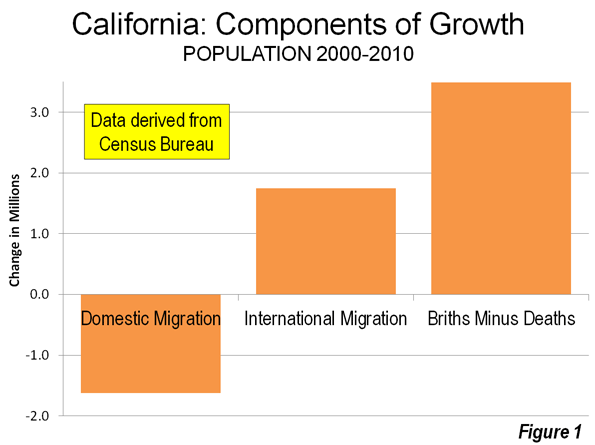

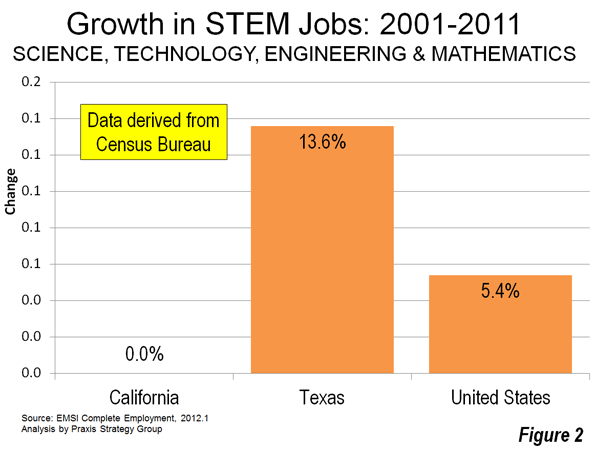

California is no longer an incubator of high-wage jobs. The state lost 370,000 jobs paying 25 percent or more of the average wage between 2000 and 2008. This compares to a 770,000 increase in

the previous 8 years. California is trailing Texas badly and the nation

overall in creating criticial STEM jobs and middle skills jobs

(Figures 2 & 3) Only two states have higher unemployment rates than

California (Nevada and Rhode Island) . California has the second highest underemployment rate

(20.8 percent), which includes the number of unemployed, plus those

who have given up looking for work ("discouraged" workers) and those

who are working only part time because they cannot find full time work.

Only Nevada, with its economy that is overly-dependent on California,

has a higher underemployment rate.

Business relocation coach Joseph Vranich conducts an annual census of companies moving jobs out of California and found a quickening pace in 2012. Often these are the very kinds of companies

capable of creating the high-wage jobs that used to be California's

forte. Vranich says that the actual number may be five times as high,

which is not surprising, not least because there is no reliable

compilation of off-shoring of jobs to places like Bangalore, Manila or

Cordoba (Argentina).

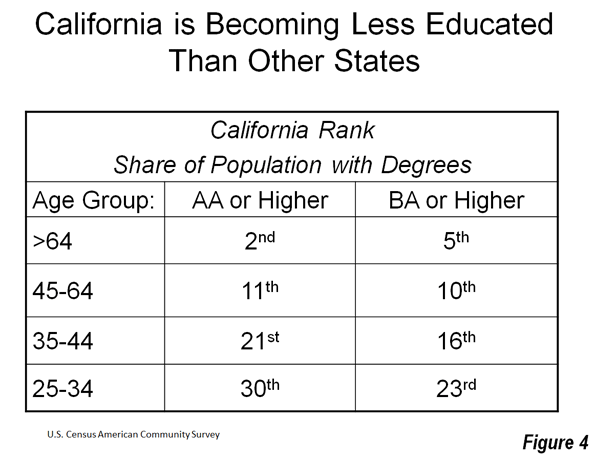

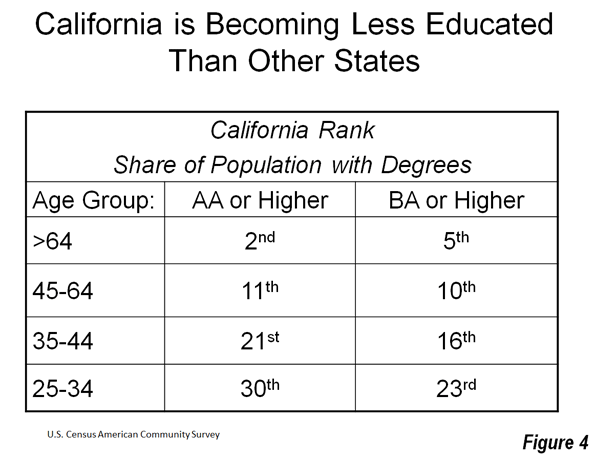

To make matters worse, California is becoming less educated.

California's share of younger people with college degrees is now about

in the middle of the states, while older, now retiring Californians are

among the most educated in the nation (Figure 4).

Denying Housing Choice

It is fantasy to believe, as Steinberg claims, that there are enough

single family (detached) houses in the state to meet the demand for

years to come. More than 80 percent of the new households in the state chose detached housing over the last decade.

People's actual choices define the market, not the theories or

preferences of planners often contemptuous of the dominant suburban

lifestyle.

In contrast, however, the regional plans adopted or under

consideration in the Bay Area, Los Angeles and San Diego would require

nearly all new housing be multi-family, at five to 10 times normal

California densities (20 or more units to the acre are being called

for). New detached housing on the urban fringe would be virtually

outlawed by these plans. And, when Sacramento does not find the

regional plans dense enough, state officials (such as the last two

state Attorneys General) are quick to sue. If the "enough detached

housing" fantasy held any water, state officials and planners would not

be seeking its legal prohibition. To call outlawing the revealed choice of the 80 percent (detached housing) would justify the equivalent of a Nobel Prize in Doublespeak.

At the same time by limiting the amount of land on which the state

preferred high density housing must be built, land and house prices can

be expected to rise even further from their already elevated levels

(already largely the result of California's pre-SB 375 regulatory

restrictions).

Transit Rhetoric and Reality

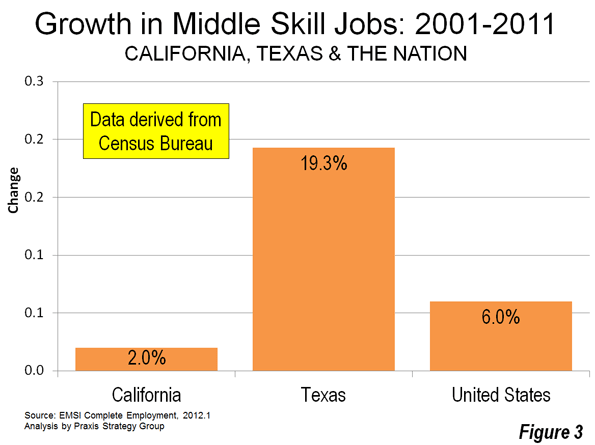

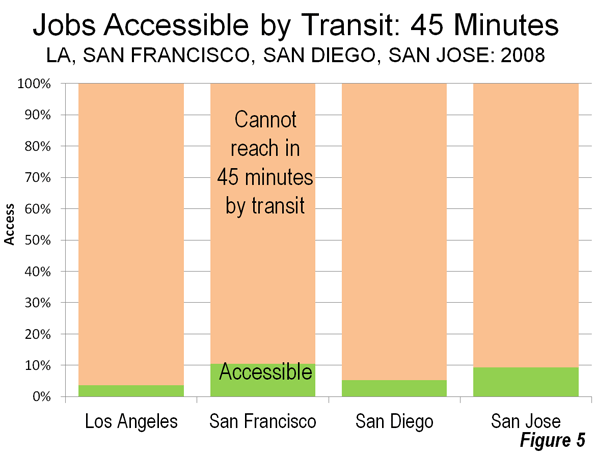

Transit is important in some markets. About one-half of commuters to

downtown San Francisco use transit. The assumptions of SB 375 might

make sense if all of California looked like downtown San Francisco. It

doesn't, nor does even most of the San Francisco metropolitan area. Only

about 15 percent of employment is downtown, while the 85 percent (and

nearly all jobs in the rest of the state) simply cannot be reached by

transit in a time that competes with the car. Even in the wealthy San

Jose area (Silicon Valley), with its light rail lines and commuter rail

line, having a transit stop nearby provides 45 minute transit access

to less than 10 percent of jobs in the metropolitan area.

A recent Brookings Institution report

showed that the average commuter in the four large coastal

metropolitan areas can reach only 6.5 percent of the jobs in a 45

minute transit commute. This is despite the fact that more than 90

percent of residents can walk to transit stops. Even when transit is

close, you can't get there from here in most cases in any practical

sense (Figure 5).

SB 375 did little to change this. For example, San Diego plans to

spend more than 50 percent of its transportation money on transit over

the next 40 years. This is 25 times transit's share of travel

(which is less than 2 percent). Yet, planners forecast that all of this

spending will still leave 7 out of 8 work and higher education trips inaccessible by

transit in 30 minutes in 2050. Already 60 to 80 percent of work trips

in California are completed by car in 45 minutes and the average travel

time is about 25 minutes.

For years, planners have embraced the ideal of balancing jobs and

housing, so that people would live near where they work, while

minimizing travel distances. This philosophy strongly drives the new SB

375 regional plans. What these plans miss is that people choose where

to work from the great array of opportunities available throughout the

metropolitan area. These varied employment opportunities that are the very reason that large metropolitan areas exist, according to former World Bank principal planner Alain Bertaud.

People change jobs far more frequently than before and multiple

earners in households are likely to work far apart. Similar intentions

led to the development up to four decades ago of centers like Tensta in

Stockholm, which ended up as concentrated low income areas (Photo). It

California, such a concentration would do little to improve transit

ridership, even low-income citizens are four to 10 times as likely use cars to get to work than to use transit.

Tensta Transit Oriented Development: Stockholm

All of this means more traffic congestion and more intense local air pollution, because higher population densities are associated with greater traffic congestion. Residents of the new denser housing would face negative health effects because there is more intense air pollution, especially along congested traffic corridors.

Self-Inflicted Wounds

Worst of all, California's radical housing and transportation strategies are unnecessary.

The unbalanced and one-dimensional pursuit of an idealized

sustainability damages both quality of life and the economy. This is

exacerbated by other issues, especially the state's dysfunctional

economic and tax policies. It is no wonder California is exporting so

many people and jobs. California's urban planning regime under SB 375

is poised to make it worse.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Art